[ad_1]

Picture by Writer | Created on Snappify

In Python, if you wish to assign values to variables inside an expression, you need to use the Walrus operator :=. Whereas x = 5 is an easy variable project, x := 5 is how you may use the Walrus operator.

This operator was launched in Python 3.8 and can assist you write extra concise and probably extra readable code (in some instances). Nonetheless, utilizing it when not crucial or greater than crucial can even make code tougher to know.

On this tutorial, we are going to discover each the efficient and the not-so-effective makes use of of the Walrus operator with easy code examples. Let’s get began!

How and When Python’s Walrus Operator is Useful

Let’s begin by examples the place the walrus operator could make your code higher.

1. Extra Concise Loops

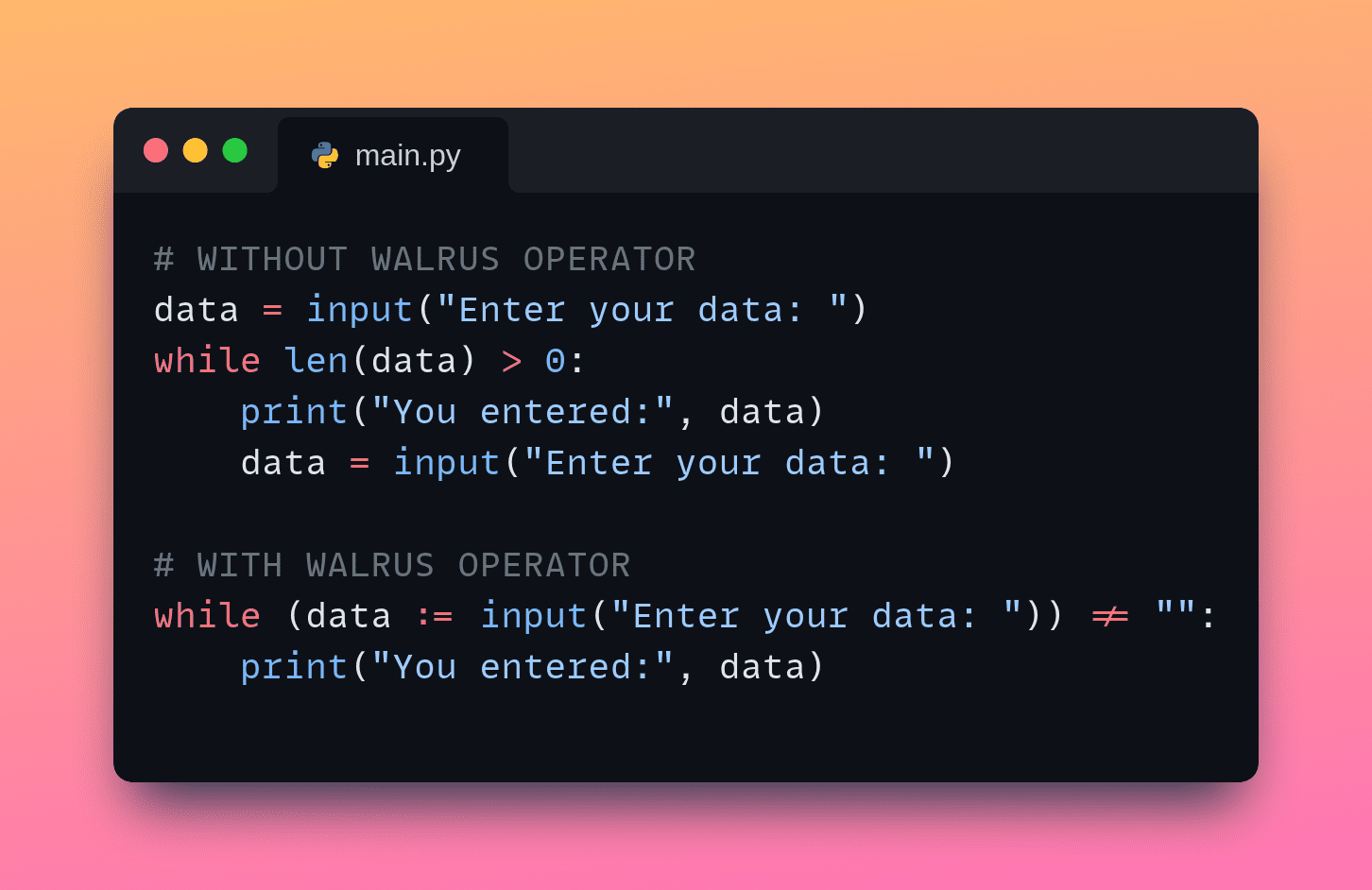

It is fairly widespread to have loop constructs the place you learn in an enter to course of inside the loop and the looping situation will depend on the enter. In such instances, utilizing the walrus operator helps you retain your loops cleaner.

With out Walrus Operator

Take into account the next instance:

knowledge = enter("Enter your knowledge: ")

whereas len(knowledge) > 0:

print("You entered:", knowledge)

knowledge = enter("Enter your knowledge: ")

If you run the above code, you’ll be repeatedly prompted to enter a price as long as you enter a non-empty string.

Notice that there’s redundancy. You initially learn within the enter to the knowledge variable. Inside the loop, you print out the entered worth and immediate the consumer for enter once more. The looping situation checks if the string is non-empty.

With Walrus Operator

You’ll be able to take away the redundancy and rewrite the above model utilizing the walrus operator. To take action, you’ll be able to learn within the enter and test if it’s a non-empty string—all inside the looping situation—utilizing the walrus operator like so:

whereas (knowledge := enter("Enter your knowledge: ")) != "":

print("You entered:", knowledge)

Now that is extra concise than the primary model.

2. Higher Checklist Comprehensions

You’ll generally have perform calls inside checklist comprehensions. This may be inefficient if there are a number of costly perform calls. In these instances, rewriting utilizing the walrus operator might be useful.

With out Walrus Operator

Take the next instance the place there are two calls to the `compute_profit` perform within the checklist comprehension expression:

- To populate the brand new checklist with the revenue worth and

- To test if the revenue worth is above a specified threshold.

# Operate to compute revenue

def compute_profit(gross sales, value):

return gross sales - value

# With out Walrus Operator

sales_data = [(100, 70), (200, 150), (150, 100), (300, 200)]

earnings = [compute_profit(sales, cost) for sales, cost in sales_data if compute_profit(sales, cost) > 50]

With Walrus Operator

You’ll be able to assign the return values from the perform name to the `revenue` variable and use that the populate the checklist like so:

# Operate to compute revenue

def compute_profit(gross sales, value):

return gross sales - value

# With Walrus Operator

sales_data = [(100, 70), (200, 150), (150, 100), (300, 200)]

earnings = [profit for sales, cost in sales_data if (profit := compute_profit(sales, cost)) > 50]

This model is best if the filtering situation entails an costly perform name.

How To not Use Python’s Walrus Operator

Now that we’ve seen just a few examples of how and when you need to use Python’s walrus operator, let’s see just a few anti-patterns.

1. Complicated Checklist Comprehensions

We used the walrus operator inside a listing comprehension to keep away from repeated perform calls in a earlier instance. However overusing the walrus operator might be simply as dangerous.

The next checklist comprehension is difficult to learn as a result of a number of nested circumstances and assignments.

# Operate to compute revenue

def compute_profit(gross sales, value):

return gross sales - value

# Messy checklist comprehension with nested walrus operator

sales_data = [(100, 70), (200, 150), (150, 100), (300, 200)]

outcomes = [

(sales, cost, profit, sales_ratio)

for sales, cost in sales_data

if (profit := compute_profit(sales, cost)) > 50

if (sales_ratio := sales / cost) > 1.5

if (profit_margin := (profit / sales)) > 0.2

]

As an train, you’ll be able to strive breaking down the logic into separate steps—inside an everyday loop and if conditional statements. It will make the code a lot simpler to learn and keep.

2. Nested Walrus Operators

Utilizing nested walrus operators can result in code that’s troublesome to each learn and keep. That is significantly problematic when the logic entails a number of assignments and circumstances inside a single expression.

# Instance of nested walrus operators

values = [5, 15, 25, 35, 45]

threshold = 20

outcomes = []

for worth in values:

if (above_threshold := worth > threshold) and (incremented := (new_value := worth + 10) > 30):

outcomes.append(new_value)

print(outcomes)

On this instance, the nested walrus operators make it obscure—requiring the reader to unpack a number of layers of logic inside a single line, decreasing readability.

Wrapping Up

On this fast tutorial, we went over how and when to and when to not use Python’s walrus operator. Yow will discover the code examples on GitHub.

When you’re searching for widespread gotchas to keep away from when programming with Python, learn 5 Frequent Python Gotchas and The best way to Keep away from Them.

Preserve coding!

Bala Priya C is a developer and technical author from India. She likes working on the intersection of math, programming, knowledge science, and content material creation. Her areas of curiosity and experience embrace DevOps, knowledge science, and pure language processing. She enjoys studying, writing, coding, and occasional! At present, she’s engaged on studying and sharing her information with the developer group by authoring tutorials, how-to guides, opinion items, and extra. Bala additionally creates partaking useful resource overviews and coding tutorials.

[ad_2]